Learn more about each of these schools from the experts themselves—the teachers working daily at the school site. Here teacher leaders from the Teacher-Powered Schools Initiative share their beginnings, challenges, and triumphs in these short reports about their schools.

Read on, or jump directly to one of the stories using the links below. You can also find more in-depth case studies on several teacher-powered schools in our guide for teachers.

- Avalon School (a teacher-powered charter school)

- Chrysalis Charter School (a teacher-powered charter school)

- Denver Green School (a teacher-powered district school)

- Avalon School empowers teachers to go beyond “sage on a stage” education

(St. Paul, Minnesota)Teacher-Powered arrangement: Chartered school contract and/or bylaws

States, counties, and school districts authorized chartered school contracts knowing that the contracts were written to formally authorize teacher autonomy. For some chartered schools, autonomy is not granted via the contract but is instead made formal via the schools’ governing bylaws. Avalon School has teachers’ authority written into its chartered school bylaws. Avalon teachers also maintain their authority because they have the majority of the school board, which is allowable under Minnesota statute.

When teachers in St. Paul, Minnesota pursued the idea of a teacher-powered school, they wanted full autonomy and authority to decide every aspect of the school structure—from hours to curriculum, from budget to selecting colleagues, and from leadership structure to discipline policies. The group of teachers decided to pursue a chartered school—one designed by teachers, operated by teachers, and inspired by students in grades 6-12. This led to the opening of Avalon, a teacher-powered charter school.

Avalon School opened in 2001, and is focused on providing all teachers and staff within the school a voice in all school-based decisions that impact student learning. Regardless of job title—whether teacher, office manager, or social worker—at Avalon, each staff and faculty member has a seat at the table and a vote on policies. The school governance operates using a 1 to 5 voting scale, in which all decisions must receive a 3 or higher rating on average to be considered for moving forward. The process, as teacher and program coordinator Carrie Bakken noted, has the respect of all involved and has never been intentionally delayed.

Student working with an advisor at Avalon

Student working with an advisor at Avalon“The process has led to high retention. We’ve maintained about a 95 percent or higher retention rate,” noted Bakken. “We also have a lot of pre-service teachers who train at Avalon and want to stay.”

The school utilizes pre-service teachers or those in transitional teaching programs as educational assistants in the classroom.

“For many, this is what they always thought teaching was like or should be,” said Bakken.

That’s exactly what Gretchen Sage-Martinson envisioned when she joined Avalon in its first year, after six years in a traditional school district.

“I saw my job in a big district as something similar to an assembly line job. People were telling me what, where, when, how to teach,” said Sage-Martinson. “I did not feel like I had entered a profession, but rather that I had become a civil servant—which isn’t in itself a bad thing, but was not what I had signed up for.”

At Avalon, Sage-Martinson spends her time as a project development facilitator to 9th through 12th grade students, helping them learn how to find reliable resources and understand the research process.

“I rarely spend time as ‘the sage on the stage’ presenting knowledge and insight for my students to digest,” she said. “I am very much a partner in their learning experience—trying to guide them ever closer to being in charge of their learning, with me as an interested, engaged bystander of the process. That’s the end goal.”

Avalon implements a self-directed, project-based learning curriculum to inspire students. Bakken believes that the self-directed learning has helped students see the relevance of their classroom learning.

Bakken and Sage-Martinson observed that students approach their learning and their teachers differently than in traditional school settings—noting that students are more cooperative, respectful and engaged in the classroom. At Avalon, students have a voice in what they learn and teachers have control to plan and adapt what they teach to students’ interests and needs. According to Sage-Martinson, students often become so engrossed in their individual projects that they become teachers to others.

Despite the obstacles over the years, such as transitioning to a new building and significant budget cuts, the school continues to thrive under its democratic process. Although, as Sage-Martinson noted, maintaining the environment while growing the school has had its challenges.

When teachers realized they needed someone who could take on more of the day-to-day administrative duties, “heated” discussions took place, at times, about what the responsibilities of a new position would mean. Faculty and staff agreed they did not want to jeopardize the collaborative nature of Avalon by creating a hierarchical position. With assistance from an outside facilitator, the group reached consensus and found a structure that has effectively served the school for more than a decade.

“It takes time and energy, which is then not directed to teaching and working with kids. You need to find that division of labor within yourself, as well as within the school,” Sage-Martinson said. “Also, you have to nurture the community, and constantly pay attention to the health of the co-op. “

Now in its thirteenth school year, Avalon’s school community is thriving in a larger school and with a greater number of students, and as one of over 150 teacher-powered schools across the nation.

“Our environment here is so healthy,” Sage-Martinson said. “We—students, staff, teachers, social workers, educational assistants—are all engaged learners working toward common goals together.”

Chrysalis Charter School allows the light within each student to shine brighter

(Palo Cedro, California)By Alysia Krafel

Teacher-Powered arrangement: Chartered school contract and/or bylaws

States, counties, and school districts authorized chartered school contracts knowing that the contracts were written to formally authorize teacher autonomy. For some chartered schools, autonomy is not granted via the contract but is instead made formal via the schools’ governing bylaws. Chrysalis Charter School has teachers’ authority written into both its chartered documents and school bylaws.

Chrysalis Charter School in Redding, California, opened in 1996 with a vision of creating a science and nature studies school where students could learn outdoors and in local museums, the community, and the classroom. Chrysalis’ goal is for students to have life experiences that confirm the world is a beautiful and fascinating place and that life is an amazing gift.

Chrysalis was intentionally created as a teacher-powered school where teachers have full autonomy and freedom to create and manage the school for the benefit of students. This autonomy was secured in the school’s charter documents and by-laws. Chrysalis teachers have control of the budget, hiring and releasing of staff and support personnel, school organization, class size, evaluation, curriculum, and the day-to-day experience of everyone in the school.

With the autonomy granted to them, teachers have created a mission statement that includes “to encourage the light within each student to shine brighter.” This means that the whole child is valued as a unique human being whose daily wellbeing at school is paramount.

Science class in the natural world

Science class in the natural worldChrysalis teachers have served this mission by creating:

- a school community with a culture of kindness and gentleness

- small class sizes with aides available to all teachers

- a child-centered curriculum that strongly stresses science and mathematics and is based on hands-on experience

- weekly field study trips out into the natural world

- an age-appropriate curriculum that values understanding over memorization and depth over breadth

- a school structure that is responsive to individual needs

- a community of parents who are invited to participate by assisting in the classroom, teaching elective classes, sitting on the executive board, and joining the Parent Club

In short, Chrysalis teachers have created a school that kids love to attend.

In the early years of Chrysalis’ operation, teachers did not have this cooperative structure. Each teacher functioned like a small business, with nearly 100 percent autonomy. The central structure served only as a shared administration. However, this structure did not allow for enough group cohesion and offered a weak mechanism for individual accountability to the group. Teachers found that this structure did not serve the school community the way they wanted, so in the 10th year of operation, a teacher cooperative structure was created.

Today, the teacher cooperative is overseen by the Chrysalis Charter School Non-profit Executive Board. This self-selected board is comprised of the school administrator, two teachers, two parents, and two at-large community members. California statute requires that the teachers on this board do not have a majority. This board has fiduciary responsibility, but they also understand that they are responsible for protecting teachers’ cooperative autonomy to lead the school.

The entire operation of the school is overseen by a charter-authorizing agency, the Shasta County Board of Education. This board provides oversight on every part of the school, but especially financial and compliance issues. They also provide business services and are trusted allies.

The school uses full-time aides in the primary grades and shared aides for upper-grade classes. “Parent teachers” are also invited into the classrooms to help out on a regular basis. Occasionally, pre-service teachers or other interns work in classrooms as well.

Chrysalis has a very high teacher retention rate. When the teachers are asked why they stay—even though the workload can be high—they typically mention autonomies like personalized instruction and academic freedom. Casey Link, a fifth-grade teacher, said, “I work at Chrysalis because I love having the freedom to meet the needs of my excited students in the immediate time frame of now.” Corrine Abert, a kindergarten teacher, added, “ I work so hard at the teacher-powered part of the school because I highly value the academic freedom in the classroom that Chrysalis gives me. It makes my work challenging but so fun.”

“Frequent and sustained immersions in

“Frequent and sustained immersions in

nature nourish the learning mind in profound ways.”

-Chrysalis, educational philosophyOne unique feature of Chrysalis’ original charter document was the “Deep Rules,” which denote the school’s organizational and cultural characteristics. Chrysalis was intentionally designed to act as a chaordic organization. This idea was created by Dee Hock, a former chairman of Visa International and the author of The Chaordic Age.

The basic idea of a chaord is that it exists in the overlap zone between order and chaos. In this space, the dance of creative growth can happen within an organization. The most important aspect of the chaordic idea as it applies to Chrysalis is that it is durable in principle but flexible in form and function. It allows innovation, shared power, and organizational learning. It is also compatible with the human spirit and the way nature works. Much of this philosophy is encapsulated within a quotation from Complexity by Michael Waldrop: “Use local control instead of global control. Let the behavior emerge from the bottom up, instead of being specified from the top down. And while you’re at it, focus on ongoing behavior instead of the final result. As Holland loved to point out, living systems never really settle down.”

These concepts drive teachers at Chrysalis to focus on ongoing behavior (Is the light shining within each student?) instead of the final result (standardized test scores). This intentional chaordic structure and culture has allowed the school to flow in a fluid form around obstacles and has enabled new people to change the way the school works. Chrysalis is expected to change and adapt to new situations, and as a result, the form of the school today is quite different from the school that started in 1996. Had it not been for this organizational aspect, teachers believe the school would not have survived the turmoil of California’s continually revised charter school laws, budget cuts, or the loss of school facilities. Instead, Chrysalis continues to successfully adapt and flow to meet the ever-changing landscape of American education while keeping students at the center of its focus. Chrysalis’ teachers are determined to always treasure and protect students’ love of learning and their growth as human beings.

Denver Green School seeds a brighter future for its students and teachers

(Denver, Colorado)Teacher-Powered arrangement: MOU & state waiver

The Math and Science Leadership Academy (MSLA) in Denver, which opened in 2009, has an MOU with the teachers union, through the Denver Public Schools school board, to have a lead teacher instead of a principal. Denver Public Schools also, specifically for MSLA, requested and received a waiver from the state of Colorado so the lead teacher has autonomy to manage the school, deal with suspensions, and do teacher evaluations. De facto the lead teacher approves decisions made collectively by MSLA teachers. This model was replicated by the Denver Green School in 2010.

After MSLA was first approved, Colorado enacted the Innovation Schools Act of 2008. The Act allows a public school or group of public schools to submit an innovation plan to its school district board of education to implement innovations that “result in improved student outcomes.” Once approved, school district boards of education must submit the innovation plans and waiver requests to the Colorado State Board of Education for ratification.

Denver Green School (DGS) opened in 2010 with the goal of innovating student learning experiences through a project-based and service learning curriculum. As one of over 120 teacher-powered schools across the country, the collective leadership—made up of seven founding partner teachers and six full partner teachers—chooses and designs their own curriculum based on math and reading, while incorporating elements of green lifestyles.

“Our school is about creating a lasting, generative impact and teaching students how to make the world a better place,” said Jeff Buck, a founding partner and sustainability coordinator at Denver Green School. “We focus on helping students learn skills like reading, writing, how to calculate and analyze information; and then, taking what they’ve learned, applying it to a solution to make positive change.”

Part of that lasting impact comes from the vision of Andrew Post, a colleague and friend of founding partner Mimi Diaz, who passed away before the school could open. As a tribute to his life, sixth-grade students designed a master plan for an outdoor memorial at the school—aptly named Andrew’s Garden — during their “summer of service” program in 2010. When DGS opened its doors that fall, students, colleagues, family and friends attended the dedication ceremony. Today, teachers have worked with experts to design curricular materials and lessons that allow students to cultivate the garden and Andrew’s teaching dream.

In 2011, DGS began a partnership with local farmers at Sprout City Farms, to house a one-acre farm site on the school property. Students participate in educational activities, summer internships, and volunteer opportunities on the grounds, while the farm provides fresh produce to the school and local needy families and food banks.

Recently, the school began another program for hands-on learning at DGS: their field studies program. A goal of the founding partners since conception of the school, teachers now take their students outside the classroom to enhance the authentic application of knowledge and skills learned in the classroom. Students visit the State Capitol, parks, go camping, and travel to learn the impact they have with those skills on a global scale.

However, making all this happen wasn’t easy.

To achieve the authority and autonomy needed to design DGS, the founding partners sought waivers through Colorado’s Innovation Schools Act, which allowed teachers to move away from the traditional school governance structure of principal management. Their local district held a seminar on proposal writing, which helped the founding partner teachers create the vision for their teacher-powered school. Once their proposal was submitted and approved by state law, teachers sought waivers from local district policy, as well as collective bargaining agreements, in order to maintain a high level of autonomy in Denver Green School.

With a focus on sustainability, the school (like other teacher-powered schools) has redesigned the schedule by extending the school day four days per week and shortening the day at the end of each week to make time for collaboration in shared governance. The teachers also designed their teacher-powered school to serve Pre-K through eighth-grade students, as well as students with special needs through its Autism Center.

Although the school’s program design must be approved by the Denver School Board, the teachers maintain a high level of authority over school operations; and their decisions have never been vetoed. Decisions about budget, schedule, curriculum, and personnel are made by the 13 full partners of the school, said Buck, but other teachers have full authority to decide how to teach in their classrooms and meet the needs of their students. The school’s partners gather input from what they refer to as the “big house,” or the entirety of school personnel, parents, students, and local leaders.

The success of Denver Green School is of no surprise when looking at their core values of community, equity, engagement, high expectations, shared leadership, stewardship and relevance. The students, teachers, and greater DGS community continue to find ways of innovating learning while creating a lasting impact.

Shared leadership at Minnesota New Country School

(Henderson, Minnesota)Teacher-Powered arrangement: Charter-TPP Contract

EdVisions Cooperative, established in 1994, is a teacher professional partnership that enters into contracts with chartered school boards. It does so across the state of Minnesota, accepting accountability for school success in exchange for its teacher-members’ authority to make decisions about the school.

With their authority the teachers determine curriculum, set the budget, choose the level of technology available to students, determine their own salaries, select their colleagues, monitor performance, and sometimes hire administrators to work for them. Each school board transfers a lump-sum to EdVisions Cooperative to carry out the contract, and expects that EdVisions will provide and oversee a site team of teachers that will carry out the EdVisions model, including project-based learning, there.

As the Teacher-Powered movement continues to gain momentum, the usual methodology for education professionals is to “follow the script.” As you read about our leadership model at Minnesota New Country School (MNCS), there are some important factors you have to know about our school community, which just celebrated its 25th year of operation:

- We need to have a sustainable model that allows staff members to work from strengths (think of learning styles for students).

- If we all share the load of administrative duties; we don’t rely on one person for the success of our school.

- Our environment is non-traditional, so the traditional leadership hierarchy was never really considered.

- We weren’t able to find a person that was able to replace our outgoing, all-world educator and administrator.

A little background for context: In December of 2013, one of our founders and educator extraordinaire, Dee Thomas, retired. She was a rare superhuman who exudes passion personally and professionally. She not only served as MNCS’ administrator, but spent 20 years in our school owning her work, including: advocacy for and promoting project based learning, connecting and promoting our school, speaking, organizing, filling out paperwork, fighting the traditional mindset of education, dealing with personnel matters, the list goes on.

Did I mention that she was an amazing, resourceful advisor (teacher) that did amazing work with students? Looking back, she was always busy in the vital work of mentoring all of us to “take over” when she left. The summer after she left, we considered and interviewed administrators as the common mantra was “we need to have someone with an administrative license.” What we found out through these conversations with candidates was that we knew our school (collectively speaking) better than anyone we could bring in. We also had to consider the salary we would have to pay someone to teach them how our school runs.

As we still needed to come up with a way to get all the work done that Dee did (including some work that we didn’t even realize she did), we discussed a great deal and finally came up with an idea to run the school by committees that would then report to the school board. Since the inception of this idea, the committees have had to become more and more accountable for their goals, plans, and work completed. This structure also allows us to prioritize work and aim efforts towards long term, academic, and non-academic goals. We allow movement on teams/committees once per year at our May staff retreat. Here is a breakdown of teams:

Professional Development Teams (PDP): Focused on students, both academic and non-academic (whole child). Includes: Math, Arts & Literature, Project Based Learning, Health & Wellness, High School/ Elementary Connections, Supporting Students Together (focused on Intervention).

Site Based Management Teams (SBM): Focused on strategic planning/goals. Includes: Personnel, Finance, Outreach, Career/Future/Technology Education, Transportation, Building, Assessment, Q-Comp, Nutrition & Composting.

Team Best Practices Include:

- All teams must elect a lead and a secretary. The lead is responsible for leadership of the group and tracking progress towards goals. The secretary takes notes for every meeting and shares highlights with the school board by the 1st Monday of the month.

- PDP teams must meet for 45 minutes every week and establish a regular, predictable meeting time (example would be Tuesdays after school at 3:30 p.m.); staff members are required to serve on at least one PDP team.

- SBM teams meet at least monthly (and as needed) during our Early Outs. These meetings are scheduled during All Staff Meetings to prevent conflicts. Staff can serve on up to two SBM teams.

- No matter the role at MNCS (teacher, para, etc.) we value your input and ask for your help in making our school successful.

Case Study on the Nutrition and Composting Team

Based on a strategic planning survey sent out to parents, staff, and students, a five year plan developed three years ago included a goal of improving and upgrading our kitchen facilities (including looking at making our own food with an emphasis on local, healthy food and becoming a more environmentally sustainable school). As these concepts have all been tinkered with by individuals, no one really owned this initiative.After the surveys and strategic planning goals were identified, we created the Nutrition and Composting team three years ago to blend people’s energies and to work on our strategic goal of upgrading our facilities—not to mention, to own these initiatives. Oversight-wise, we are accountable to our Charter School Authorizer to both show that we are planning and meeting our strategic goals.

We have many staff members and parents who are passionate about our food, particularly giving our students healthy options to nourish their bodies. Equally important: we had people on staff who were passionate about making our school more environmentally friendly, including focusing on things like recycling, composting, and reducing waste. While the team has inevitably gone down some dead ends in regards to having an in-house, sustainable food program, they have many accomplishments to celebrate over the last three years, including:

- Making mock menus and recipes that included pricing and taste testing;

- Connecting with resources in the community to further explore local food partnerships;

- Thanks to the herculean efforts by Carrie Rice (General Education Para), we moved to reusable/sustainable serving trays and utensils rather than using paper plates and plastic utensils;

- A faculty member obtained their Food Safety certification;

- We saved 7,000 plates, bowls, and plastic utensils from going into landfills during the 2018-19 school year;

- Kitchens at both the Elementary and High School have been updated with proper requirements for washing dishes (hand washing sinks, triple sinks, dishwasher);

- Both sites compost food waste, and;

- We have free breakfast options for every student K-12.

While the efforts of the Nutrition and Composting team were tremendous, they also inspired other staff members and teams to accomplish their work. To have the funding, the team had to work with both the Building and Finance teams to move forward. We are moving closer and closer to having our own in-house option for student meals.

All of the above goals happened because people owned the work and put huge efforts in making them happen. Too often, hierarchical leadership models dissuade initiative as people at the top take the credit for the ideas and goals that get accomplished. It is the space between the idea and accomplishment that we also celebrate. MNCS has always operated on the idea that if you see a problem that needs to be fixed, you have to be willing to help solve the problem and try ideas—to put your money where your mouth is.

Does Collective Leadership Work?

It is definitely a more sustainable model to operate an organization. We make better decisions when we get the input of colleagues. While we continue to tweak our leadership model, we do have leaders who have risen to the top of the organization. Essentially, these are teachers who have exemplified “owing the work.” We have been looking at other schools’ models of leadership and trying to come to a consensus on whether we need to make a change. This leadership conversation will continue to go through tweaks, side conversations, and initiatives as the years go by. Some ideas that we have been considering as a staff are based on schools like Avalon School in St. Paul:- Create Co-Administrator positions for up to 3 teachers who would share identified administrative duties, as well as continuing to serve as a teacher (to stay connected to students);

- Let the Co-Administrative positions be three year terms, as to provide staffing flexibility and to prevent burnout;

- Come up with a method that is fair for identifying the teachers to serve in the Co-Administrative role, and;

- Consider what strengths we want to prioritize for these positions, like data savvy, organization, ability to deal with parents, student relationships, staff relationships, etc.

Teacher-powered Social Justice Humanitas Academy

(Los Angeles, California)By Jeff Austin

Teacher-Powered arrangement: Pilot school agreements

In 2007, the United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) and the surrounding community launched the Belmont Zone of Choice, modeled after Boston Pilot Schools. After initial success, UTLA “overwhelmingly” voted to expand the number of schools in 2009. In 2010 a new Kennedy Zone of Choice emerged and in 2013 a third option opened in the Sotomayor Zone of Choice. In 2015, there are now 18 Zones of Choice that house small school options for students including 50 pilot schools in Los Angeles. Some of these pilot schools have chosen to have teacher-powered school governance structures.

The Center for Collaborative Education (CCE) developed the Five Conditions of Autonomy for schools that are espoused in both the Boston and Los Angeles pilot school agreements (memorandums of understanding, or MOUs), which are arranged between the school district and the union. The five conditions include: staffing, budget, curriculum & assessment, governance, and school calendar. In addition to the MOU, teachers at each Boston and Los Angeles pilot school collectively write an Elect to Work Agreement (EWA) for their site on an annual basis that outlines the working conditions at the school. In Los Angeles, these EWAs are also approved by their union, UTLA. This is a means to exercise more autonomy at the school level, at the will of the teachers.

The EWA is voted on by the teachers at the site, and teachers who do not agree to work under the conditions will enter the district’s hiring pool and default to the working conditions outlined in the existing collective bargaining agreement.

Part of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the Social Justice Humanitas Academy (SJHA) is one of four high schools on the Cesar E. Chavez Learning Academies campus in San Fernando, CA. SJHA is a teacher-powered pilot school serving 520 students in grades 9-12. Its student body is 94% Latino, with 87% qualifying for free or reduced lunch and 80% speaking English as a second language. SJHA students face not only the poverty and language barriers visible in the numbers, but also many of the challenges associated with low-income communities – gangs, drugs, violence, lack of access to resources, and the consistent low expectations within and outside their community.

Despite low expectations within and outside their community,

Despite low expectations within and outside their community,

SJHA students and teachers boast a 94% graduation rateSJHA started in 2000 as the Multimedia Academy Small Learning Community at Sylmar High School. Initially, the school consisted of three teachers who taught interdisciplinary lessons in English, Art, and History. Sixty students voluntarily chose to be part of this alternative program. The Multimedia Academy changed to the Humanitas Academy after partnering with Los Angeles Education Partnership’s (LAEP) Humanitas Network of schools, and expanded to three grade-level teams in 2006. In 2010, it became a full 9-12, semi-autonomous academy, serving approximately 500 students.

LAUSD first permitted the creation of Pilot Schools in 2007 through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with United Teachers Los Angeles. In 2009, this program expanded with the Public School Choice program that opened up management of new schools to any groups who submitted applications and completed a public voting process. Humanitas teachers learned about this opportunity for greater autonomy and began pushing for this option with Ramon Cortines, the superintendent at that time. Because there was a cap on the number of pilot schools, Humanitas teachers and other teacher groups in the LAEP Humanitas network advocated for a cap increase with the UTLA House of Representatives.

After a heated battle, the cap was increased and the opportunity for Humanitas to become a pilot school became a reality. Humanitas teachers wrote a proposal in response to a Request For Proposals outlined in LAUSD’s Public School Choice 2.0 process. Eleven teams, including teacher teams, teams of district administrators and charter operators, sought the opportunity to directly manage and direct the vision of four new small schools to be opened on the Cesar E. Chavez Campus in LAUSD’s Northeast Valley Zone of Choice (ZoC). After a series of community meetings and a round of voting, the SJHA proposal was recommended by Cortines and then approved by the LAUSD school board, along with two other pilot schools and one district-led small school. SJHA opened its doors to 510 high school students in the fall of 2011.

Today, students are admitted to SJHA through the ZoC. Students living within the boundaries of the ZoC can choose to attend any of the seven high schools in that zone. As students complete eighth grade, their schools assist them in filling out online applications and listing their high school preferences. The parents sign a printed copy, and applications are then entered into a random, computer-generated draw. Students are also allowed a one-time transfer after completing ninth grade.

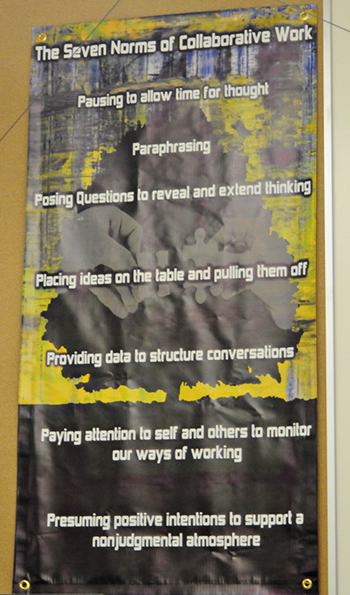

A painted hallway at SJHA: teachers have created a student-centered

A painted hallway at SJHA: teachers have created a student-centered

school by taking advantage of curriculum and assessment autonomyA Memorandum of Understanding between LAUSD and the teachers’ union, United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) waives aspects of the collective bargaining agreement to provide that SJHA can have its own governing board that makes decisions using the five pilot school autonomies: budget, governance, staffing, curriculum and assessment, and calendar. These five autonomy areas were originally defined as essential by the Center for Collaborative Education (CCE) as a result of its observations of successful Boston pilot schools, some of which have been in existence since the mid-1990s. At SJHA, the governing board informally transfers its decision-making authority to teachers, but provides oversight to ensure that SJHA teachers are meeting their mission, vision, values, and goals, which include accountability for the outcomes of their decisions.

How does this play out in practice? Using their governance autonomy, SJHA teachers define their own working conditions annually in an Election-to-Work Agreement (EWA). The team then seeks approval for their agreement from UTLA (which has never been a problem), and each individual is asked to sign on to the terms each year. At SJHA, the teacher team has decided the terms include the following: creating specific curricular requirements, working additional hours to support students, taking on leadership roles within the school, and beginning the National Board Certification process by their fifth year at the school. Each year, teachers can choose not to sign the EWA, or the school can choose not to offer an EWA to a teacher, both resulting in the teacher moving to another LAUSD school. The EWA is probably the most significant tool SJHA has to do things differently from most LAUSD schools.

SJHA teachers have taken advantage of curriculum and assessment autonomy to create a student-centered school with a rigorous and engaging curriculum presented with thoughtful, researched instructional techniques. Compared to previous experiences in a traditionally-governed school, teachers are now able to be more responsive to student needs in purchasing textbooks, choosing course offerings, and making University of California A-G requirements the standard for high school graduation.

The staffing and governance autonomies allow SJHA Leadership to have increased (although still limited) control over staffing of the school, including administration. Each year the Governing Council evaluates the Principal (and a new administrative position opening in 2015-16) and decides whether he/she will be retained. Any member of the teaching staff who does not meet the requirements can also be “excessed” back into the LAUSD hiring pool. The current principal, who became a principal to get this position and believes in a teacher-powered vision, has been retained every year, and no teachers have been excessed. The goal of SJHA Leadership is to build a cohesive team that increases its instructional and leadership capacity every year. This could not be done if the school continually replaced members of the teaching staff.

With budget autonomy, the teaching team is able to selectively allocate all the funds that come to SJHA according to the district per-pupil funding model. Other LAUSD schools are mandated to purchase certain teacher and school administrator positions using standardized position costs—in other words, all teachers cost the same despite their actual salaries, and some positions are automatically created at the school site based on the number of students. At SJHA, teachers decide to count only actual salaries (as they are defined by the district-union contract) when creating the school budget. The team also allocates funds for positions needed for student success. This means there is an incentive for the school to hire new, inexperienced teachers. However, SJHA and its staff are committed to building the strongest teaching team possible. Making hiring decisions based on potential salary would be contrary to the vision and mission of this school. Indeed, many of the teachers who started SJHA are also the most expensive. The staff has become a mix of experienced SJHA teachers and teachers both new to SJHA and new to teaching. Experienced staff bring a depth of institutional knowledge of the ideas, structures, and plans (those that succeeded and those that failed) that led the school to where it is today while newer teachers bring a fresh, energetic perspective based on their experiences at other schools. Together, these two groups make up a staff with multiple perspectives, all empowered to lead the school towards the vision.

SJHA teacher teams embrace the mindset that

SJHA teacher teams embrace the mindset that

everyone is an “ally in waiting,” as they must

constantly advocate for using autonomies

afforded to them through the pilot agreement.

The wall hanging can be found in the school’s

Collaboration Room, which is open to both

teachers and students.The autonomies afforded to SJHA through the pilot agreement have, in many ways, allowed the teacher team to create the kind of school it has always suspected would lead to student success. Yet it’s not all moonlight and roses. SJHA is a pioneer in this work at LAUSD, and that means the teaching team must constantly advocate for itself to show how its unconventional decisions are within the purview of the school’s five autonomies. In other words, the team must consider district and union politics as well as the time and energy required to advocate for these autonomies. In this sense, SJHA teachers are only able to use the autonomies to an extent. This is a common experience for teacher-powered schools that function in district and union settings. The SJHA team knows this is part of the work of change, and even embraces the mindset that everyone is an “ally in waiting.” Still, the team experiences highs and lows through its successes and struggles in this aspect of its duties.

One struggle has been the team’s perception that LAUSD and union leaders have been slow to adjust management structures and policies to accommodate the intentional diversification of how schools are governed. For example, although LAUSD refers to pilot schools as teacher led (meaning, collaboratively led by the team of teachers), its management structures and policies still put the administrator at the heart of every decision. Although it has been eight years, when someone from central office or UTLA calls the school, he asks to talk to the principal (who, in practice, is selected by the teacher team). Perhaps due to a conservative interpretation of how the pilot autonomies can be used, district administrators assert that teachers can only counsel one another on issues of curriculum and instruction. When there are issues involving non-curricular guidelines, teachers are not allowed to officially counsel each other. When teachers struggle with instruction, collaboration with their colleagues, or in building relationships with students, administrators are expected to unilaterally document and take administrative action, instead of building capacity in collaboration with the entire school staff.

The SJHA team does not believe that district and union leaders have a deliberate intention to sabotage the changes the team is advancing inside its walls. There does, however, seem to be an expectation on the part of district-level administrators that all schools run the same way. Dealing with that expectation becomes a significant part of what pilot schools do. The SJHA team prefers to make the time and energy investment about whether the district understands this problem and is actively seeking solutions. In the team’s ideal world, district and union leaders would be consulting regularly with pilot school teams to learn how to support them better in the pilot school agreements and the management practices.

Despite these struggles, the numbers show that teachers’ hard work—including their decisions about how to best use the five autonomies–is paying off. SJHA boasts a 94% graduation rate, the highest student and teacher attendance in LAUSD, 80% university eligibility, and California Exit Exam pass rates well above the LAUSD average. SJHA is one of LAUSD’s Restorative Justice model schools – having only had two suspensions and zero expulsions in four years of operation, and in 2015 was named a National Community School of Excellence. The school has been featured in several publications including Corwin Press’s Growing Into Equity. Members of the staff have spoken at several national conferences, and staff members have had their own writing published by educational press.

The less quantitative data shows even more: the resiliency of SJHA students, the relationships between staff and students, and students who describe the school as their home and SJHA’s staff members as their family. This belief in relationships has allowed SJHA to move closer to its vision by having teacher leaders with close knowledge of student needs while being empowered to make the changes at the school level to meet those needs. This has helped SJHA become an incredibly successful teacher-powered school with students who experience academic rewards and achievement.

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP